Asthma / Allergic Rhinitis

Get In Touch

Call Now

Monday to Friday

9:00 AM To 6:00 PM

Saturday and Sunday

Closed

Overview

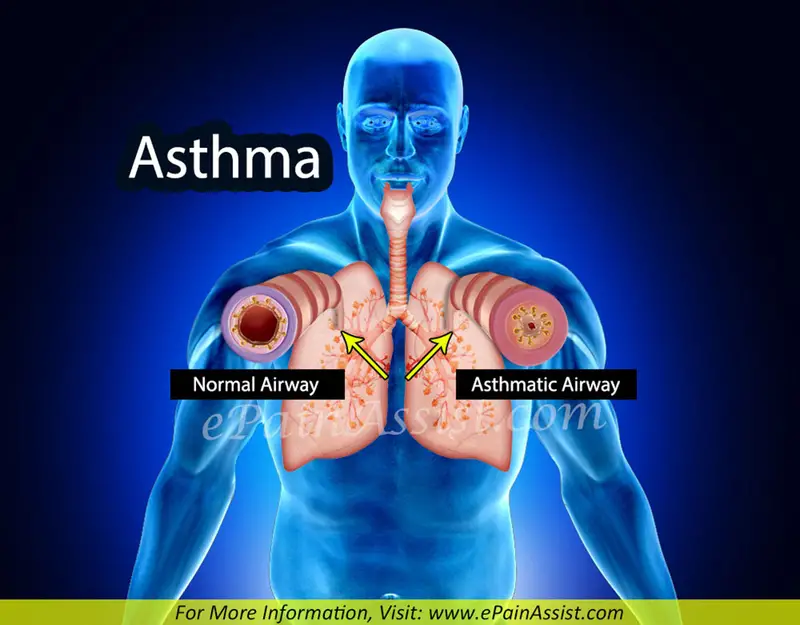

- Asthma is a common long-term inflammatory disease of the airways of the lungs.

- It is characterized by variable and recurring symptoms, reversible airflow obstruction, and easily triggered bronchospasms.

- Symptoms include episodes of wheezing, coughing, chest tightness, and shortness of breath. These may occur a few times a day or a few times per week. Depending on the person, asthma symptoms may become worse at night or with exercise.

- Asthma is thought to be caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

- exposure to air pollution and allergens.

- Medications such as aspirin and beta blockers.

- Diagnosis is usually based on the pattern of symptoms, response to therapy over time, and spirometrylung function testing.

- Asthma is classified according to:

- Frequency of symptoms, Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and peak expiratory flow rate.

- It may also be classified as atopic or non-atopic (atopy refers to a predisposition toward developing a type 1 hypersensitivity reaction).

- There is no cure for asthma.

- Symptoms can be prevented by

- Avoiding triggers, such as allergens and irritants,

- Use of inhaled corticosteroids.

- Use of Long-acting beta agonists (LABA) or antileukotriene agents in addition to inhaled corticosteroids if asthma symptoms remain uncontrolled.

- Treatment of rapidly worsening symptoms is usually with an inhaled short-acting beta-2 agonist such as salbutamol and corticosteroids taken by mouth. In very severe cases, intravenous corticosteroids, magnesium sulfate, and hospitalization

Signs And Symptoms

- Asthma is characterized by recurrent episodes of wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and coughing.

- Sputum may be produced from the lung by coughing but is often hard to bring up. During recovery from an asthma attack (exacerbation), it may appear pus-like due to high levels of white blood cells called eosinophils. Symptoms are usually worse at night and in the early morning or in response to exercise or cold air. Some people with asthma rarely experience symptoms, usually in response to triggers, whereas others may react frequently and readily and experience persistent symptoms.

Several other health conditions occur more frequently in people with asthma, including

- Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease (GERD),

- Rhinosinusitis Obstructive sleep apnea.

- Psychological disorders are also more common

- Anxiety disorders occurring in between 16–52%

- Mood disorders in 14–41%. It is not known whether asthma causes psychological problems or psychological problems lead to asthma.

- radiocontrast reactions in those with asthma, especially if it is poorly controlled.

Causes

- Asthma is caused by a combination of complex and incompletely understood environmental and genetic interactions.

- These influences both its severity and its responsiveness to treatment.

- It is believed that the recent increased rates of asthma are due to

- changing epigenetics (heritable factors other than those related to the DNA sequence) and a

- changing living environment.

- Asthma that starts before the age of 12 years old is more likely due to genetic influence, while onset after age 12 is more likely due to environmental influence.

Environmental

- Many environmental factors have been associated with asthma’s development and exacerbation, including,

- allergens, air pollution, and other environmental chemicals.

- Smoking during pregnancy and after delivery is associated with a greater risk of asthma-like symptoms.

- Low air quality from environmental factors such as traffic pollution or high ozone levels.

- Over half of cases in children in the United States occur in areas when air quality is below the EPA standards. Low air quality is more common in low-income and minority communities.

- Exposure to indoor volatile organic compounds may be a trigger for asthma; formaldehyde exposure, for example, has a positive association.

- Acetaminophen use by a mother during pregnancy is also associated with an increased risk of the child developing asthma.

- Maternal psychological stress during pregnancy is a risk factor for the child to develop asthma.

- Asthma is associated with exposure to indoor allergens.

- Common indoor allergens include dust mites, cockroaches, animal dander (fragments of fur or feathers), and mold.

- Efforts to decrease dust mites have been found to be ineffective on symptoms in sensitized subjects.

- Weak evidence suggests that efforts to decrease mold by repairing buildings may help improve asthma symptoms in adults.

- Certain viral respiratory infections, such as respiratory syncytial virus and rhinovirus, may increase the risk of developing asthma when acquired as young children. Certain other infections, however, may decrease the risk.

Hygiene Hypothesis

- The hygiene hypothesis attempts to explain the increased rates of asthma worldwide as a direct and unintended result of reduced exposure, during childhood, to non-pathogenic bacteria and viruses.

- It has been proposed that the reduced exposure to bacteria and viruses is due, in part, to increased cleanliness and decreased family size in modern societies. Exposure to bacterial endotoxin in early childhood may prevent the development of asthma, but exposure at an older age may provoke bronchoconstriction.

- Evidence supporting the hygiene hypothesis includes lower rates of asthma on farms and in households with pets.

- Use of antibiotics in early life has been linked to the development of asthma.

- Delivery via caesarean section is associated with an increased risk (estimated at 20–80%) of asthma – this increased risk is attributed to the lack of healthy bacterial colonization that the newborn would have acquired from passage through the birth canal.

- There is a link between asthma and the degree of affluence which may be related to the hygiene hypothesis as less affluent individuals often have more exposure to bacteria and viruses.

Genetic

- Family history is a risk factor for asthma, with many different genes being implicated

- If one identical twin is affected, the probability of the other having the disease is approximately 25%.

- By the end of 2005, 25 genes had been associated with asthma in six or more separate populations.

- Many of these genes are related to the immune system or modulating inflammation.

- In 2006 over 100 genes were associated with asthma in one genetic association study alone, more continue to be found.

- Some genetic variants may only cause asthma when they are combined with specific environmental exposures.

- An example is a specific single nucleotide polymorphism in the CD14 region and exposure to endotoxin (a bacterial product).

- Endotoxin exposure can come from several environmental sources including tobacco smoke, dogs, and farms. Risk for asthma, then, is determined by both a person’s genetics and the level of endotoxin exposure.

Medical Conditions Associated With Asthma

- A triad of atopic eczema, allergic rhinitis and asthma is called atopy. The strongest risk factor for developing asthma is a history of atopic disease; with asthma occurring at a much greater rate in those who have either eczema or hay fever.

- Asthma has been associated with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis an autoimmune disease and vasculitis.

- Individuals with certain types of urticaria may also experience symptoms of asthma.

- There is a correlation between obesity and the risk of asthma with both having increased in recent years. Several factors may be at play including decreased respiratory function due to a buildup of fat and the fact that adipose tissue leads to a pro-inflammatory state.

- Beta blocker medications such as propranolol can trigger asthma in those who are susceptible.

- Other medications that can cause problems in asthmatics are angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, aspirin, and NSAIDs.

- Use of acid suppressing medication (proton pump inhibitors and H2 blockers) during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of asthma in the child.

Exacerbation

- Some individuals will have stable asthma for weeks or months and then suddenly develop an episode of acute asthma.

- Different individuals react to various factors in different ways.

- Most individuals can develop severe exacerbation from several triggering agents:

- Home factors that can lead to exacerbation of asthma include dust, animal dander (especially cat and dog hair), cockroach allergens and mold. Perfumes are a common cause of acute attacks in women and children.

- Both viral and bacterial infections of the upper respiratory tract can worsen the disease.

- Psychological stress may worsen symptoms – it is thought that stress alters the immune system and thus increases the airway inflammatory response to allergens and irritants.

- Asthma exacerbations in school‐aged children peak in autumn, shortly after children return to school. This might reflect a combination of factors, including poor treatment adherence, increased allergen and viral exposure, and altered immune tolerance.

Pathophysiology

How Asthma Occurs (Bronchospasm)

- Asthma is the result of chronic inflammation of the conducting zone of the airways (most especially the bronchi and bronchioles), which subsequently results in increased contractibility of the surrounding smooth muscles. This among other factors leads to bouts of narrowing of the airway and the classic symptoms of wheezing.

- The narrowing is typically reversible with or without treatment.

- Occasionally the airways themselves change. Typical changes in the airways include an increase in eosinophils and thickening of the lamina reticularis. Chronically the airways’ smooth muscle may increase in size along with an increase in the numbers of mucous glands. Other cell types involved include: T lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils. There may also be involvement of other components of the immune system including: cytokines, chemokines, histamine, and leukotrienes among others.

Diagnosis

- There is currently no precise test for the diagnosis, which is typically based on the pattern of symptoms and response to therapy over time.

- A diagnosis of asthma should be suspected if there is a history of recurrent wheezing, coughing or difficulty breathing and these symptoms occur or worsen due to exercise, viral infections, allergens or air pollution.

- Spirometry is then used to confirm the diagnosis.

- In children under the age of six the diagnosis is more difficult as they are too young for spirometry.

- Spirometry is recommended to aid in diagnosis and management.

- It is the single best test for asthma.

- If the FEV1 measured by this technique improves more than 12% and increases by at least 200 milliliters following administration of a bronchodilator such as salbutamol, this is supportive of the diagnosis.

- It however may be normal in those with a history of mild asthma, not currently acting up.

- As is a bronchodilator in people with asthma, the use of caffeine before a lung function test may interfere with the results.

- Single-breath diffusing capacity can help differentiate asthma from COPD It is reasonable to perform spirometry every one or two years to follow how well a person’s asthma is controlled.

- The methacholine challenge involves the inhalation of increasing concentrations of a substance that causes airway narrowing in those predisposed. If negative it means that a person does not have asthma; if positive, however, it is not specific for the disease.

- Other supportive evidence includes: a ≥20% difference in peak expiratory flow rate on at least three days in a week for at least two weeks, a ≥20% improvement of peak flow following treatment with either salbutamol, inhaled corticosteroids or prednisone, or a ≥20% decrease in peak flow following exposure to a trigger.

Classification

Asthma is clinically classified according to:

- The frequency of symptoms,

- Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1)

- Peak expiratory flow rate.

Asthma may also be classified as

- Atopic (extrinsic) based on symptoms are precipitated by allergens (atopic)

- Non-atopic (intrinsic), based on whether or not (non- atopic).

While asthma is classified based on severity, at the moment there is no clear method for classifying different subgroups of asthma beyond this system. Finding ways to identify subgroups that respond well to different types of treatments is a current critical goal of asthma research.

Although asthma is a chronic obstructive condition, it is not considered as a part of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, as this term refers specifically to combinations of disease that are irreversible such as bronchiectasis and emphysema.

Unlike these diseases, the airway obstruction in asthma is usually reversible; however, if left untreated, the chronic inflammation from asthma can lead the lungs to become irreversibly obstructed due to airway remodeling. In contrast to emphysema, asthma affects the bronchi, not the alveoli.

Clinical classification (≥ 12 years old)

| Severity | Symptom Frequency | Night-time Symptoms | %FEV1 Predicted | FEV1 Variability | Albuterol Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intermittent | ≤2/week | ≤2/month | ≥80% | <20% | ≤2 days/week |

| Mild Persistent | 2/week | 3–4/month | ≥80% | 20–30% | 2 Days/week |

| Moderate Persistent | Daily | 1/week | 60–80% | 30% | Daily |

| Severe Persistent | Continuous | Frequent (7/week) | <60% | 30% | ≥Twice/day |

Asthma Exacerbation

- An acute asthma exacerbation is commonly referred to as an asthma attack.

- The classic symptoms are shortness of breath, wheezing, and chest tightness.

- The wheezing is most often when breathing out.

- Signs occurring during an asthma attack include:

- use of accessory muscles of respiration (sternocleidomastoid and scalene muscles of the neck),

- there may be a paradoxical pulse (a pulse that is weaker during inhalation and stronger during exhalation)

- Over-inflation of the chest.

- A blue color of the skin and nails may occur from lack of oxygen.

- In a mild exacerbation the peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) is ≥200 L/min, or ≥50% of the predicted best. Moderate is defined as between 80 and 200 L/min, or 25% and 50% of the predicted best, while severe is defined as ≤ 80 L/min, or ≤25% of the predicted best.

- Acute severe asthma (previously known as status asthmaticus)

- Is an acute exacerbation of asthma that does not respond to standard treatments of bronchodilators and corticosteroids.

- Half of cases are due to infections with others caused by allergen, air pollution, or insufficient or medication use.

- Brittle asthma is a kind of asthma distinguishable by recurrent, severe attacks.

- Type 1 brittle asthma is a disease with wide peak flow variability, despite intense medication.

- Type 2 brittle asthma is background well-controlled asthma with sudden severe exacerbations.

- Exercise-induced Asthma Exercise Induced Bronchoconstriction

- Exercise can trigger bronchoconstriction both in people with or without asthma.

- It occurs in most people with asthma and up to 20% of people without asthma.

- Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction is common in professional athletes. The highest rates are among cyclists (up to 45%), swimmers, and cross-country skiers.

- While it may occur with any weather conditions, it is more common when it is dry and cold.

- Inhaled beta2-agonists do not appear to improve athletic performance among those without asthma Occupational

- Occupational asthma

- Asthma as a result of (or worsened by) workplace exposures is a commonly reported occupational disease.

- Many cases, however, are not reported or recognized as such.

- It is estimated that 5–25% of asthma cases in adults are work-related.

- A few hundred different agents have been implicated, with the most common being: isocyanates, grain and wood dust, colophony, soldering flux, latex, animals, and aldehydes.

- The employment associated with the highest risk of problems include: those who spray paint, bakers and those who process food, nurses, chemical workers, those who work with animals, welders, hairdressers and timber workers.

- Aspirin-induced asthma Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease

- Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD), also known as aspirin-induced asthma, affects up to 9% of asthmatics.

- AERD consists of asthma, nasal polyps, sinus disease, and respiratory reactions to aspirin and other NSAID medications (such as ibuprofen and naproxen).

- People often also develop loss of smell and most experience respiratory reactions to alcohol.

- Alcohol-induced asthmaAlcohol-induced respiratory reactions

- Alcohol may worsen asthmatic symptoms in up to a third of people.

- This may be even more common in some ethnic groups such as the Japanese and those with aspirin-induced asthma.

Non-atopic asthma

- Non-atopic asthma, also known as intrinsic or non-allergic, makes up between 10 and 33% of cases. There is negative skin test to common inhalant allergens and normal serum concentrations of IgE.

- Often it starts later in life, and women are more commonly affected than men. Usual treatments may not work as well.

Differential Diagnosis

- Many other conditions can cause symptoms like those of asthma.

- In children, other upper airway diseases such as allergic rhinitis and sinusitis should be considered

- Other causes of airway obstruction including Foreign body aspiration, Tracheal stenosis, laryngotracheomalacia, vascular rings, enlarged lymph nodes or Neck masses.

- Bronchiolitis and other viral infections may also produce wheezing.

- In adults, COPD, Congestive heart failure, airway masses, as well as drug-induced coughing due to ACE inhibitors should be considered.

- In both populations vocal cord dysfunction may present similarly.

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease can coexist with asthma and can occur as a complication of chronic asthma.

- After the age of 65, most people with obstructive airway disease will have asthma and COPD.

- In this setting, COPD can be differentiated by increased airway neutrophils, abnormally increased wall thickness, and increased smooth muscle in the bronchi.

- However, this level of investigation is not performed due to COPD and asthma sharing similar principles of management: corticosteroids, long-acting beta-agonists, and smoking cessation.

- It closely resembles asthma in symptoms, is correlated with more exposure to cigarette smoke, an older age, less symptom reversibility after bronchodilator administration, and decreased likelihood of family history of atopy.

Prevention

- The evidence for the effectiveness of measures to prevent the development of asthma is weak.

- The World Health Organization recommends decreasing risk factors such as tobacco smoke, air pollution, chemical irritants including perfume, and the number of lower respiratory infections.

- Other efforts that show promise include: limiting smoke exposure in utero, breastfeeding, and increased exposure to daycare or large families, but none are well supported enough to be recommended for this indication.

- Early pet exposure may be useful. Results from exposure to pets at other times are inconclusive and it is only recommended that pets be removed from the home if a person has allergic symptoms to said pet.

- Dietary restrictions during pregnancy or when breast feeding have not been found to be effective at preventing asthma in children and are not recommended. Reducing or eliminating compounds known to sensitive people from the work place may be effective. It is not clear if annual influenza vaccinations affects the risk of exacerbations. Immunization, however, is recommended by the World Health Organization. Smoking bans are effective in decreasing exacerbations of asthma.

Management

- While there is no cure for asthma, symptoms can typically be improved.

- A specific, customized plan for proactively monitoring and managing symptoms should be created. This plan should include the reduction of exposure to allergens, testing to assess the severity of symptoms, and the usage of and adjustments to medications.

- The treatment plan should be written down and advise adjustments to treatment according to changes in symptoms.

- The most effective treatment for asthma is identifying triggers, such as cigarette smoke, pets, or aspirin, and eliminating exposure to them.

- If trigger avoidance is insufficient, the use of medication is recommended. Pharmaceutical drugs are selected based on, among other things, the severity of illness and the frequency of symptoms. Specific medications for asthma are broadly classified into

- Fast-acting and Long-acting categories.

- Bronchodilators are recommended for short-term relief of symptoms. In those with occasional attacks, no other medication is needed.

- If mild persistent disease is present (more than two attacks a week), low-dose inhaled corticosteroids or alternatively, a leukotriene antagonist or a mast cell stabilizer by mouth is recommended.

- For those who have daily attacks, a higher dose of inhaled corticosteroids is used. In a moderate or severe exacerbation, corticosteroids by mouth are added to these treatments.

- People with asthma have higher rates of anxiety, psychological stress, and depression. This is associated with poorer asthma control. Cognitive behavioral therapy may improve quality of life, asthma control, and anxiety levels in people with asthma.

- Improving people’s knowledge about asthma and using a written action plan has been identified as an important component of managing asthma. Providing educational sessions that include information specific to a person’s culture is likely effective. More research is necessary to determine if increasing preparedness and knowledge of asthma among school staff and families using home-based and school interventions results in long term improvements in safety for children with asthma. Lifestyle modification

- Avoidance of triggers is a key component of improving control and preventing attacks. The most common triggers include allergens, smoke (from tobacco or other sources), air pollution, non selective beta-blockers, and sulfite-containing foods. Cigarette smoking and second-hand smoke (passive smoke) may reduce the effectiveness of medications such as corticosteroids. Laws that limit smoking decrease the number of people hospitalized for asthma. Dust mite control measures, including air filtration, chemicals to kill mites, vacuuming, mattress covers and others methods had no effect on asthma symptoms. There is insufficient evidence to suggest that dehumidifiers are helpful for controlling asthma.

Medications

- Medications used to treat asthma are divided into two general classes:

- Quick-relief medications used to treat acute symptoms

- Long-term control medications used to prevent further exacerbation.

- Antibiotics are generally not needed for sudden worsening of symptoms or for treating asthma at any time.

Fast Acting

- Salbutamol metered dose inhaler commonly used to treat asthma attacks.

- Salbutamol metered dose inhaler commonly used to treat asthma attacks.

- Short-acting beta2-adrenoceptor agonists (SABA), such as salbutamol (albuterol USAN) are the first line treatment for asthma symptoms. They are recommended before exercise in those with exercise induced symptoms. Anticholinergic medications, such as ipratropium, provide additional benefit when used in combination with SABA in those with moderate or severe symptoms and may prevent hospitalizations.

- Anticholinergic bronchodilators can also be used if a person cannot tolerate a SABA. If a child requires admission to hospital additional ipratropium does not appear to help over a SABA.

- For children over 2 years old with acute asthma symptoms, inhaled anticholinergic medications taken alone is safe but is not as effective as inhaled SABA or SABA combined with inhaled anticholinergic medication.

- Adults who receive combined inhaled medications that includes short-acting anticholinergics and SABA may be at risk for increased adverse effects such as experiencing a tremor, agitation, and heart beat palpitations compared to people who are treated with SABA by itself.

- Older, less selective adrenergic agonists, such as inhaled epinephrine, have similar efficacy to SABAs. They are however not recommended due to concerns regarding excessive cardiac stimulation.

- A short course of corticosteroids after an acute asthma exacerbation may help prevent relapses and reduce hospitalizations. For adults and children who are in the hospital due to acute asthma, systematic (IV) corticosteroids improve symptoms.

Long–term control

- Fluticasone propionate metered dose inhaler commonly used for long-term control.

- Corticosteroids are generally considered the most effective treatment available for long-term control.

- Inhaled forms such as beclomethasone are usually

- In the case of severe persistent disease, in which oral corticosteroids may be needed. It is usually recommended that inhaled formulations be used once or twice daily, depending on the severity of symptoms,

- Long-acting beta-adrenoceptor agonists (LABA) such as salmeterol and formoterol can improve asthma control, at least in adults, when given in combination with inhaled corticosteroids.

- Leukotriene receptor antagonists (anti-leukotriene agents such as montelukast and zafirlukast) may be used in addition to inhaled corticosteroids, typically also in conjunction with a LABA.

- For adults or adolescents who have persistent asthma that is not controlled very well, the addition of anti-leukotriene agents along with daily inhaled corticosteroids improves lung function and reduces the risk of moderate and severe asthma exacerbations. Anti-leukotriene agents may be effective alone for adolescents and adults, however there is no clear research suggesting which people with asthma would benefit from anti-leukotriene receptor alone.

- Intravenous administration of the drug aminophylline does not provide an improvement in bronchodilation when compared to standard inhaled beta-2 agonist treatment. Aminophylline treatment is associated with more adverse effects compared to inhaled beta-2 agonist treatment.

- Mast cell stabilizers (such as cromolyn sodium) are another non-preferred alternative to corticosteroids.

- For children with asthma which is well-controlled on combination therapy of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and long-acting beta2-agonists (LABA), the benefits and harms of stopping LABA and stepping down to ICS-only therapy are uncertain.

Other Treatments

When asthma is unresponsive to usual medications, other options are available for both emergency management and prevention of flareups. Additional options include:

- Oxygen to alleviate hypoxia if saturations fall below 92%

- Corticosteroid by mouth are recommended with five days of prednisone being the same 2 days of dexamethasone. One review recommended a seven-day course of steroids.

- Magnesium sulfate intravenous treatment

- increases bronchodilation when used in addition to other treatment in moderate severe acute asthma attacks.

- In adults intravenous treatment results in a reduction of hospital admissions.

- Low levels of evidence suggest that inhaled (nebulized) magnesium sulfate may have a small benefit for treating acute asthma in adults.

- Heliox, a mixture of helium and oxygen, may also be considered in severe unresponsive cases.

- Intravenous salbutamol is not supported by available evidence and is thus used only in extreme cases.

- Methylxanthines (such as theophylline)

- were once widely used, but do not add significantly to the effects of inhaled beta-agonists.

- Their use in acute exacerbations is controversial.

- ketamineThe dissociative anesthetic

- is theoretically useful if intubation and mechanical ventilation is needed in people who are approaching respiratory arrest; however, there is no evidence from clinical trials to support this.

- bronchial thermoplastic

- For those with severe persistent asthma not controlled by inhaled corticosteroids and LABAs, may be an option.

- It involves the delivery of controlled thermal energy to the airway wall during a series of bronchoscopies.

- While it may increase exacerbation frequency in the first few months it appears to decrease the subsequent rate.

- Effects beyond one year are unknown.

- Monoclonal antibody injections such as mepolizumab, ruplizumab, or omalizumab

- may be useful in those with poorly controlled atopic asthma.

- However, as of 2019 these medications are expensive, and their use is therefore reserved for those with severe symptoms to achieve cost-effectiveness.

- sublingual immunotherapy in those with both allergic rhinitis and asthma improve outcomes.

- The prognosis for asthma is generally good, especially for children with mild disease.

- While asthma is twice as common in boys as girls, severe asthma occurs at equal rates

- In contrast adult women have a higher rate of asthma than men and it is more common in the young than the old.

What Patients Say

Our Testimonials

Why patients trust Dr. Farah with their health

Came in with a headache and started to feel sick. Had a big trip for New Years, therefore I had to solve my problems quickly. Dr. Farah helped me right away and treated all my problems, he saved my weekend. Will come here again soon.

Melanie Warner

I was in a lot of pain and I walked in and the receptionist was so lovely. I was into see the doctor within five minutes and he listened to me and was wonderful. I’ve been to a few urgent cares and this one by far is the best !

Tiffany Lee-Frank

I absolutely love Dr Farah and his whole staff on the medical and the spa side. I’m not just saying this, Dr Farah has been my doctor over 10 years and I’ve been using his Rejuvenate spa for about 4 years now. I would give them 10 stars if I could!!!

Lori Brooks

Ashley and Anna are friendly and made me feel welcome and at ease. Dr. Farah was very understanding and answered all my stupid questions. They were all very professional and patient with me.

juli ross

Providing Urgent Care for non-life-threatening health complications

Urgent care services

Monday to Friday

9:00 AM To 6:00 PM

Saturday and Sunday

Closed

17130 Ventura Boulevard,

Encino California 91316